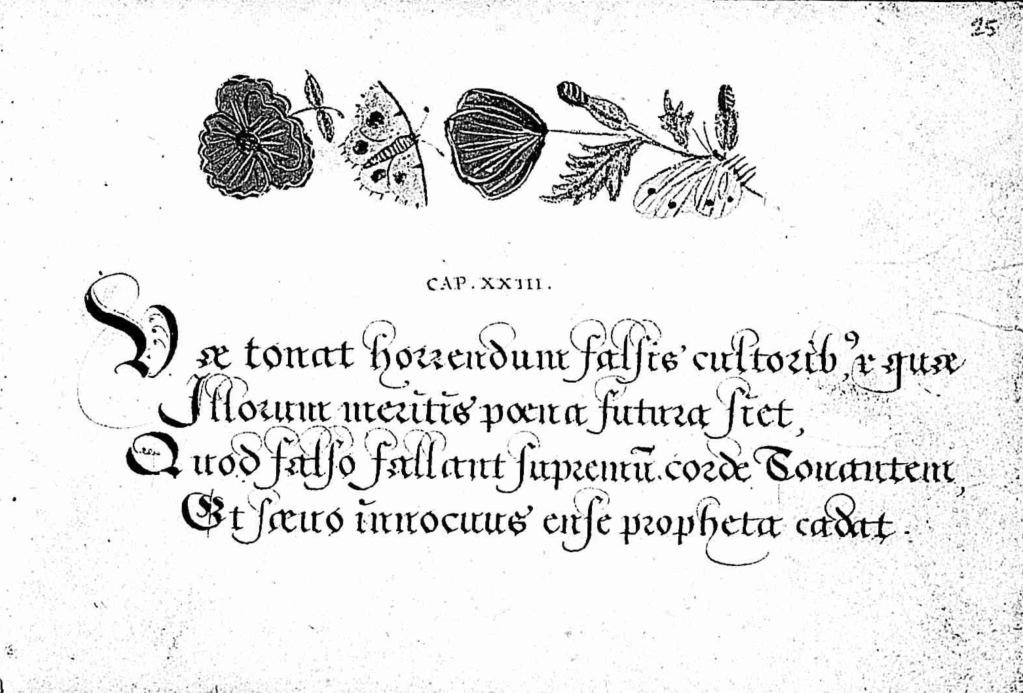

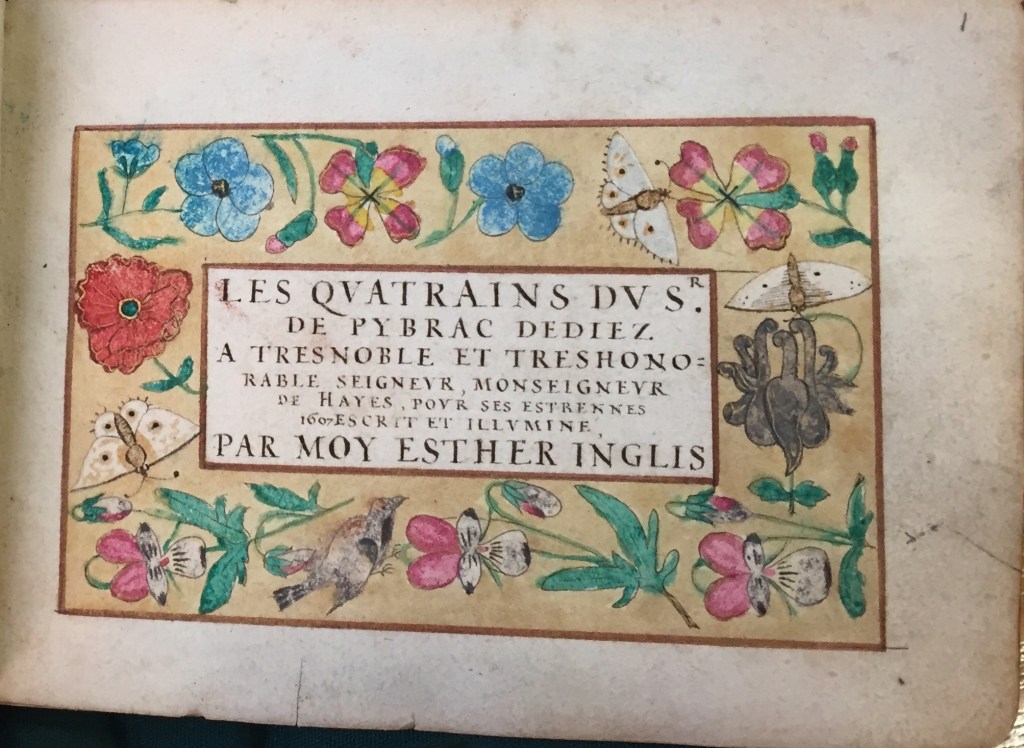

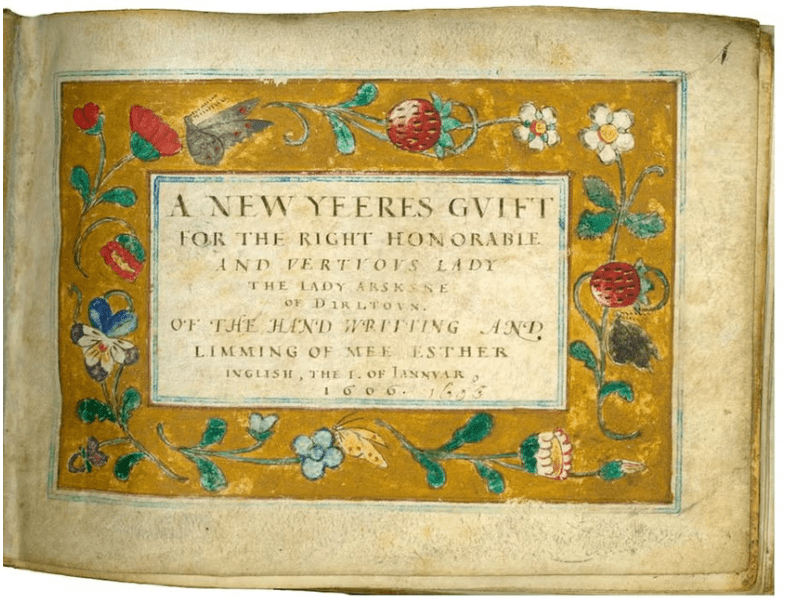

Esther Inglis and Bartilmo Kello were married in 1596 and had at least eight children, possibly nine. Unlike many women of the period, Esther seems to have timed her pregnancies about every two years, which undoubtedly made it easier for her to work. Some of her whimsical moths, birds, caterpillars, and snails suggest she was aware of how her art could appeal to children as well.

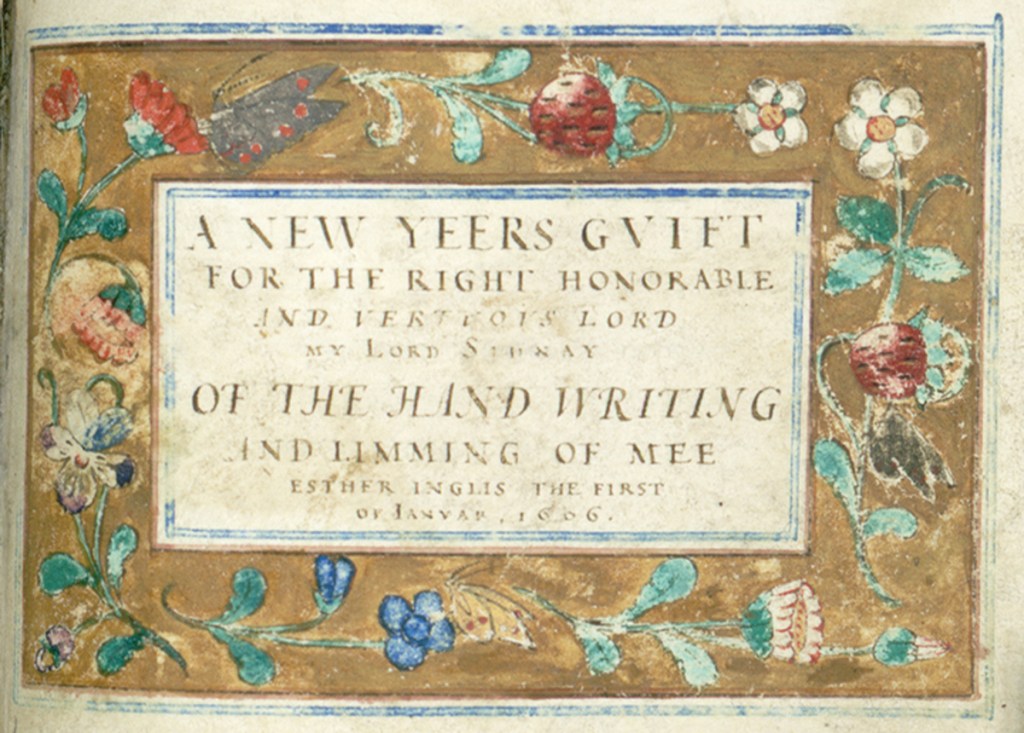

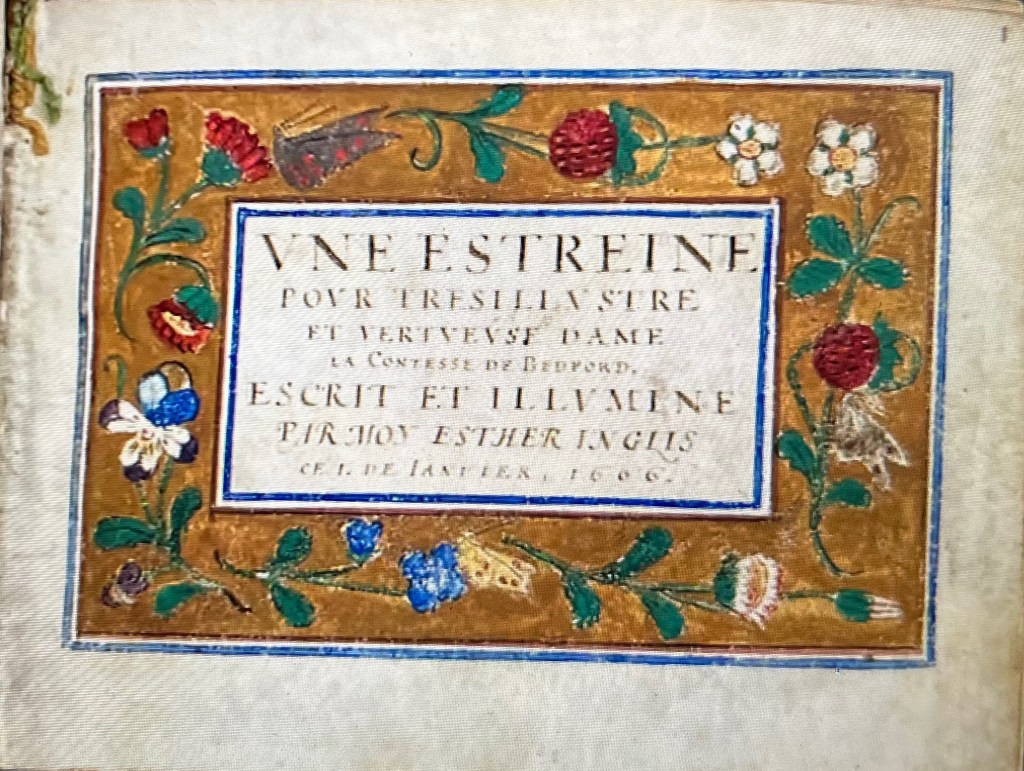

Houghton Library MS Typ 212, 1606.

Esther’s ‘Very Hungry Caterpillar’! Houghton Library MS Typ 212, 1606.

Here is a list of the children of Esther and Bartilmo, with their baptismal dates.*

13 March 1597, Edinburgh: twins Samuel and Agnes; Agnes evidently died soon after as she disappears from the records; Samuel lived until 1680 as minister at Spexhall in Suffolk.

13 May 1599, Edinburgh: Jeane – she may have died young also as we don’t hear about her in the records.

1 March 1601, Edinburgh: Josephe – died at age thirteen, 30 September 1614, Willingale Spain.

[no record ca. 1602], Edinburgh: Hester – marries James Crighton of Lochbank in 1618; they have six children.

8 March 1605, London: Isaake – died at age nine, 13 July 1614, Willingale Spain.

6 November 1608, Willingale-Spain: Elizabeth – appears in Edinburgh Registers of Sasines from 1620.

[7 April 1610, Willingale Spain: Margaret – father recorded as John Kello, but no other Kellos are found in that parish, so this may be a mistake by the registrar]

12 May 1612, Willingale Spain: Marie – marries Patrick Ainslie, merchant burgess of Edinburgh, December 1632 – he mistreats her.

*I am immensely grateful to Jamie Reid Baxter for trolling through many records to find these children.