Calligrapher, limner, embroiderer, writer – those are all arts in which Esther Inglis engaged. She seems to have been unique in Britain at the time, so who were her cohorts?

There must have been other contemporary British women who were multi-talented, but it’s not easy to find them. Certainly upper-class women, including queens Elizabeth and Mary of Scots, learned to embroider and often had handwriting lessons, but they didn’t use their talents professionally.

Mary Queen of Scots monogram. Museum no. T.29-1955. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Jane Segar, Enamel on velvet front binding from British Library, Add. MS 10037

Then there was Jane Segar, from an artistic family, who wrote out her own poems on the Sibylls in a beautiful hand, and bound them in a jewel-like enamel binding for Queen Elizabeth, but this work seems to be unique.1

To find really multi-talented professional women artists working on a scale similar to Esther’s we need to turn to the continent, and especially, the Netherlands. Many of them will be found in an exhibition on now (until Jan. 11, 2026) at the National Museum of Women in the Arts: “Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600-1750.”2

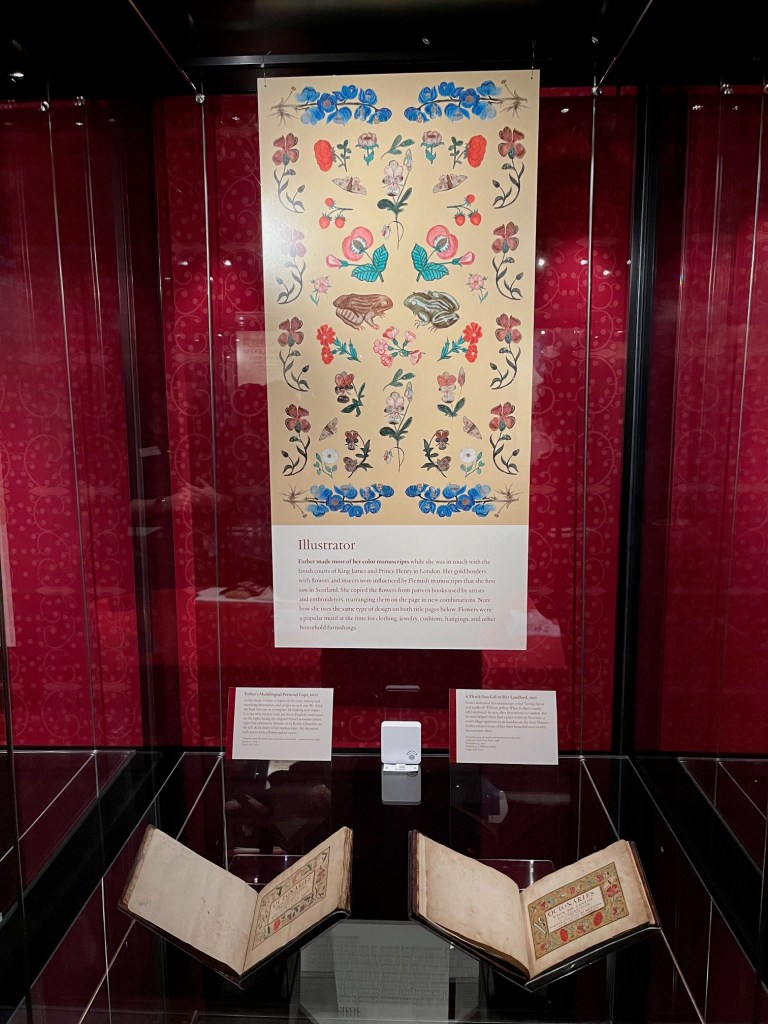

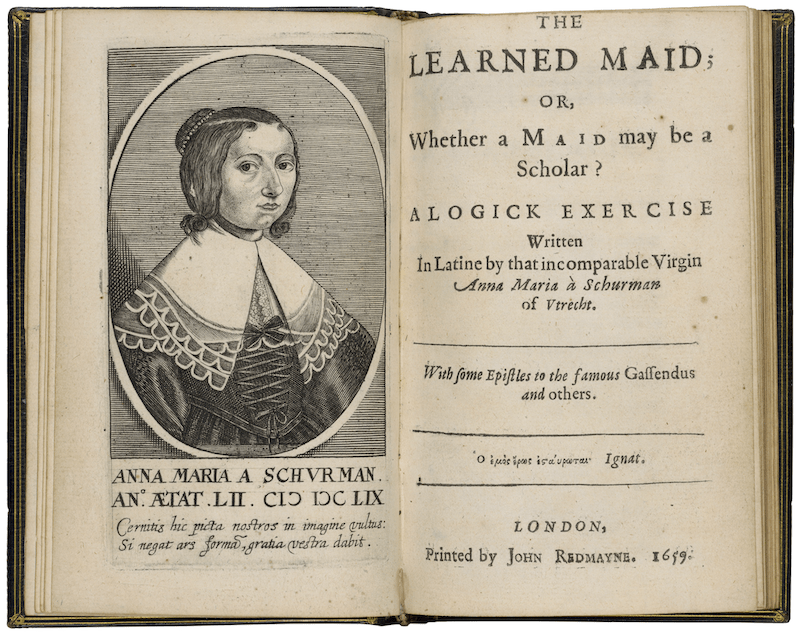

Most of these women were from professional families; some like Esther had a father who was an educator. Often other members of their family were involved in the arts, like Esther’s calligrapher mother Marie Presot, and many were multi-talented. One of the best-known is Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678), a scholar, writer and calligrapher who also made drawings, and engraved on copper and glass.

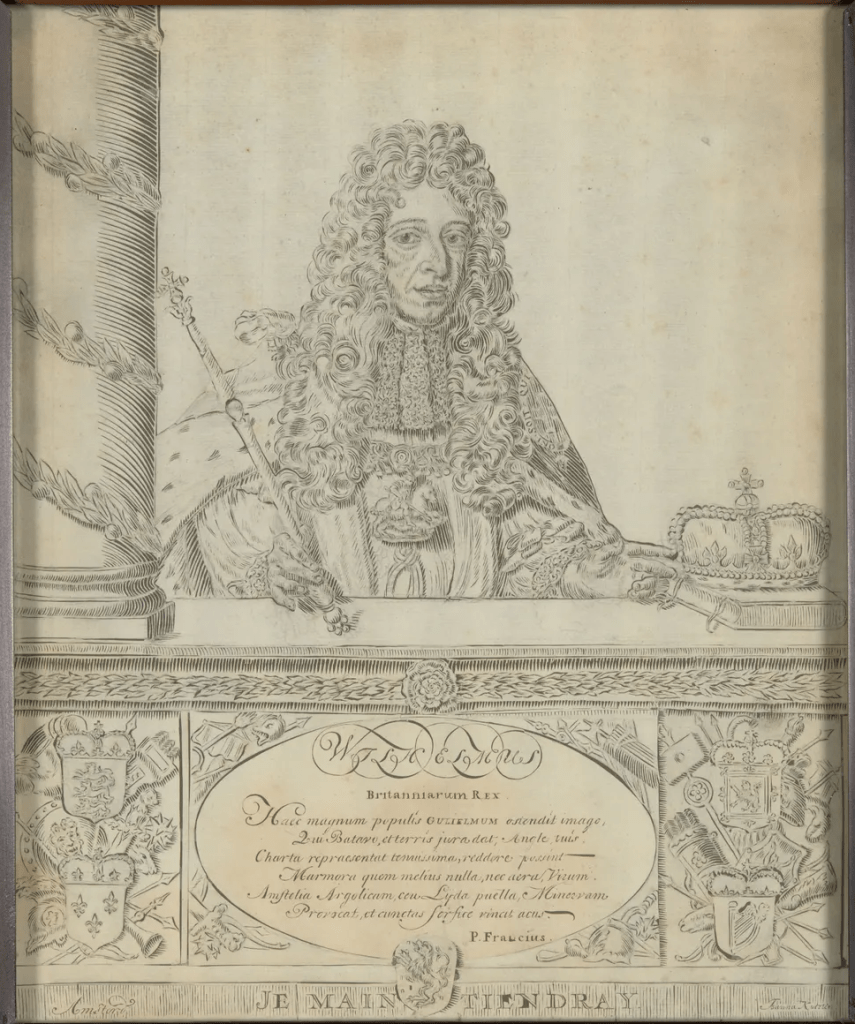

English translation of Schurman’s work, with engraving of her self portrait. First published in Latin in 1641, then in London in 1659. Folger Shakespeare Library.

Then there is Margaretha van Godewijck, known only by reputation, since her works are lost. Her talents were described by Arnold Houbraken in his Great Theatre of Dutch Painters and Paintresses (1718): “She was able to stitch landscapes, farms, houses, flowers and all kinds of ships, as well as paint everyting in oil and water paints. . . She was also able laudably to depict all sorts of objects in pen and pencil, [and] could further write inventively on glass . . . .”[3]

More than 40 versatile women artists—painters, sculptors, embroiderers, lacemakers, printmakers, papercutters—are featured in the exhibition and catalogue, along with self portraits. Esther Inglis was the first woman in Britain to include self portraits with her works, but she had a forerunner in Catharina van Hemessen (1548), the first European artist of either sex to create a self portrait.3 After Hemessen, many other Dutch women artists, including van Schurman and Judith Leyster followed suit.

Like Hemessen, Esther shows herself at work with the tools of her trade: pen, ink, and paper. Schurman never shows her hands actually creating. Apparently she was taken to task for that by Constantijn Huygens, the statesman and poet, who thought she should be proud of her ink-stained hands.4

Esther Inglis, Self portrait drawn with pen and ink, 1602 (NLS MS 20498); Schurman, Engraved self portrait, 1640 (NMWA, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay)

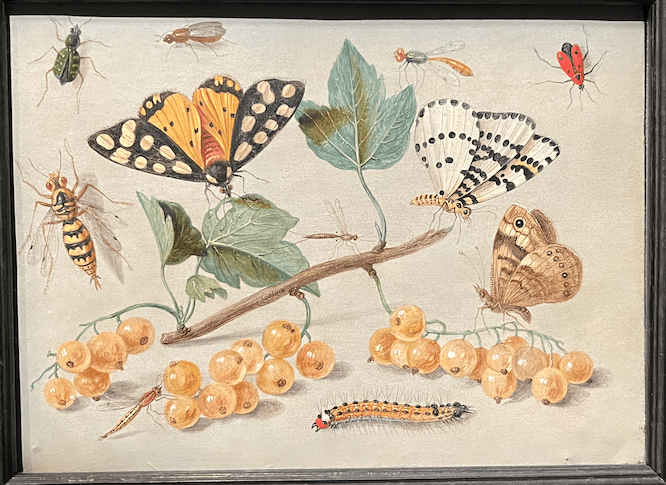

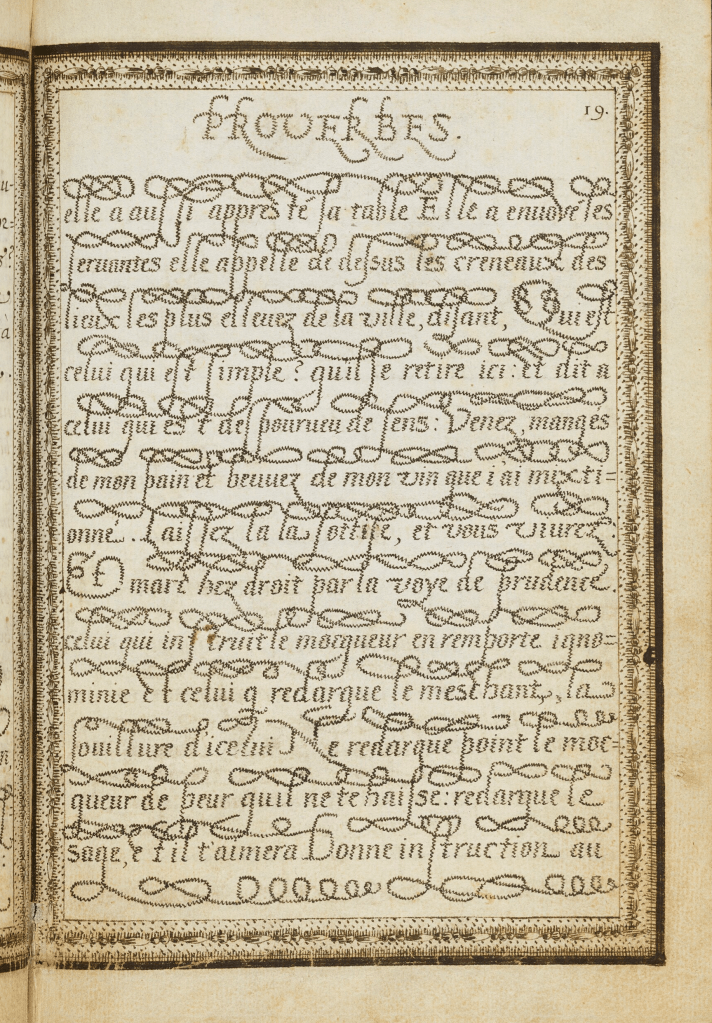

As we saw with Godewijck, some of these women were praised for embroidering with such skill that it looked like painting. Several handwriting styles used by Esther make the letters look as though they were stitched to the page. Similarly, the amazingly fine cut-paper work created by several of these artists, most especially Johanna Koerten (1650-1715), achieves the effect of pen-and-ink drawing produced by Esther and others of these Dutch artists.

As a Franco-Scot, Esther Inglis was herself of continental origin, part of that wave of talented immigrants who poured into England and Scotland during the Protestant Reformation. Artists, goldsmiths, jewelers, calligraphers, printers, engravers, weavers—men and women—they enriched British society in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with their artistic contributions. To find Esther’s female peers, we do well to look to France and the Netherlands.

- On Segar see Susan Frye, Pens and Needles: Women’s Textualities in Early Modern England (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010). ↩︎

- Unforgettable: Women Artists from Antwerp to Amsterdam, 1600-1750, ed. Virginia Treanor and Frederica Van Dam (Ghent: Hannibal Books, 2025). ↩︎

- Treanor, p.27. ↩︎

- NMWA website: https://nmwa.org/art/collection/schurman-self-portrait/ ↩︎