The National Gallery of Art in Washington DC has recently opened an exhibition titled “Little Beasts; Art, Wonder, and the Natural World.” I had my first slow walk-through yesterday and plan to return – maybe more than once!

It’s a small but marvelous exhibition focusing on sixteenth and seventeenth-century artists from the Netherlands who became passionate and detailed observers of the natural world, especially butterflies, moths, shells, and insects, but also larger animals, often strange ones from foreign shores. As the Dutch developed an extensive mercantile trade, they came into contact with new and exotic objects, often obtained for them by the efforts of the native peoples in the countries they visited, many in South Asia.

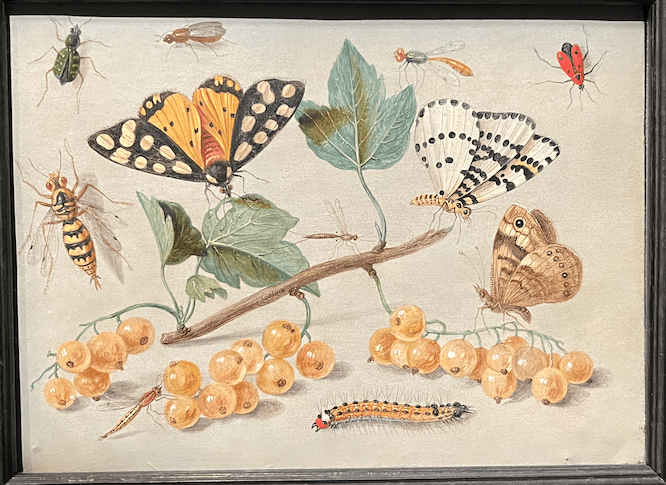

First focusing on Joris Hoefnagel (1542-1600), the exhibition details his working methods, and displays amazing examples from his watercolour series, “The Four Elements.” Then it moves on to his later counterpart, Jan van Kessel (1626-1679) who continued Hoefnagel’s studies in oil on copper. The NGA smartly partnered with the Smithsonian Museum of Natural HIstory to borrow specimens of actual animals, insects, and shells, shown alongside the artistic representations.

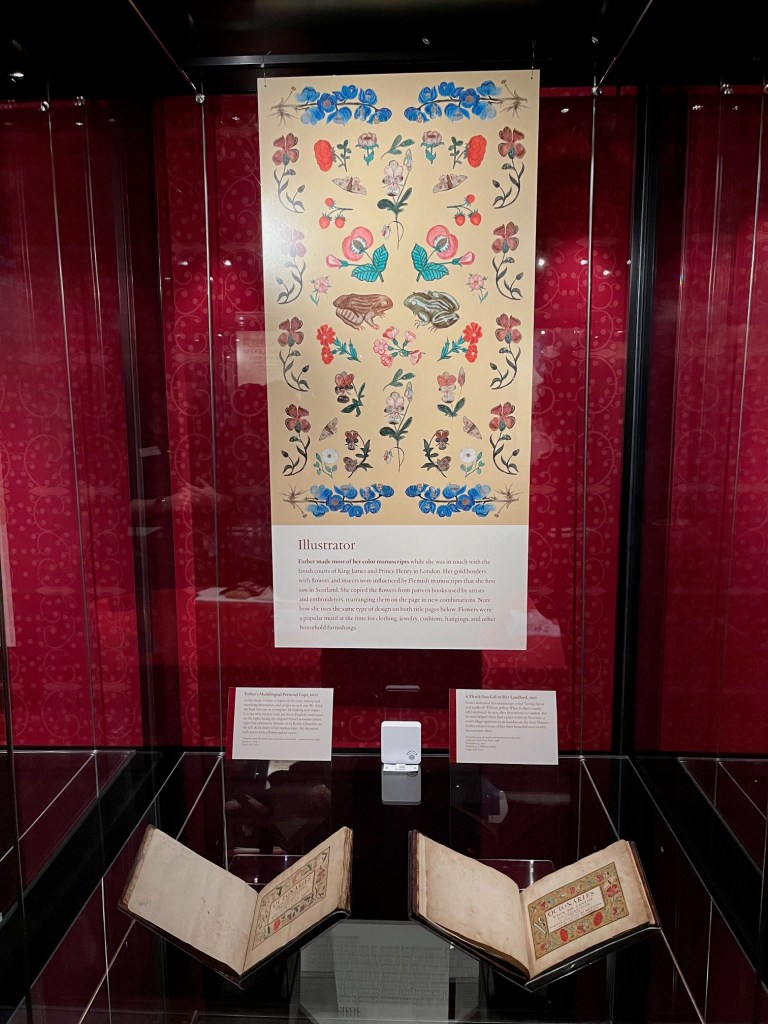

As soon as I walked in, I thought of Esther Inglis who used the same kinds of pigments as Hoefnagel – powdered red, green, and blue from natural sources mixed in shells – and similar brushes, samples of which are on display.

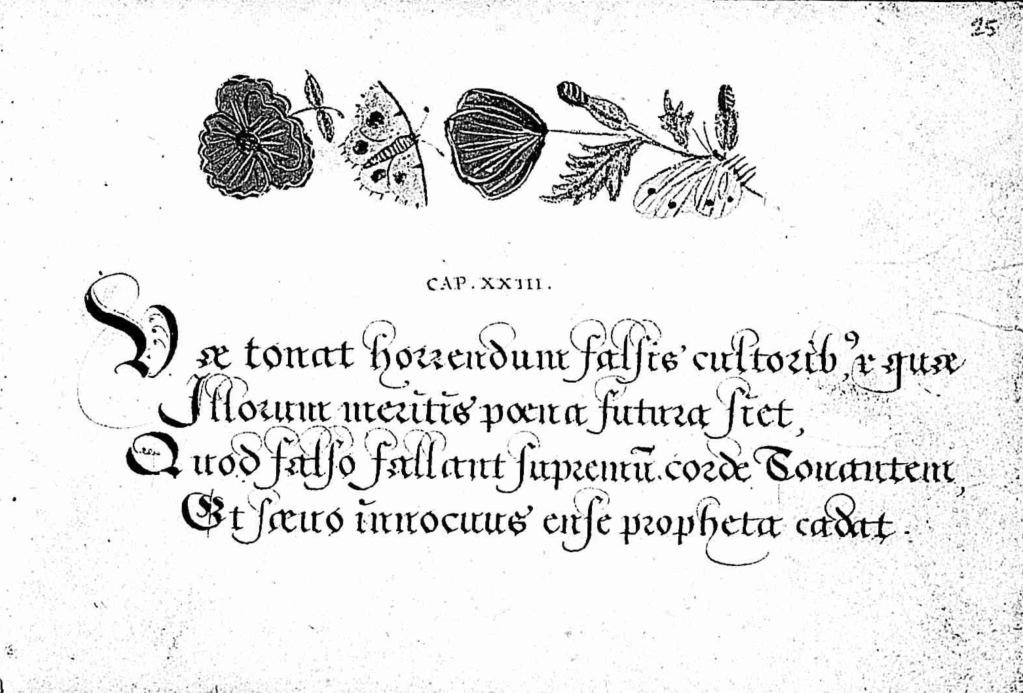

And Esther’s constant pairing of biblical and moral texts with her flowers, butterflies, birds, and frogs puts her in direct conversation with Hoefnagel and others at the time who “paired many drawings with Latin inscriptions of Bible verses, bits of poetry, mottos, or proverbs.” For them, the natural world was all a manifestation of God’s creation.

Flemish women artists were major contributors to floral works that often contained small insects, snails, or other creatures. An exquisite painting by Clara Peeters (c.1587-after 1636), features as the only work by a woman in the exhibition.

She and Michaelina Wautier (c.1604-1689) were contemporaries of Esther Inglis, though Esther would not likely have seen their work. They were followed by Maria van Oosterwijck (1630-1693) and Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) among others, plus the many women who painted with watercolour on paper, such as botanical artist Alida Withoos. For more about them, see the blog posts by Ariane van Suchtelen “Women and the Art of Flower Painting”, and by Catherine Powell, “Alida Withoos: Creator of beauty and of visual knowledge.”

We can assume that Esther Inglis would have enjoyed their company as she festooned her own works with flowers and critters from the same kinds of engravings copied by artists such as Hoefnagel and van Kessel. See my Folger blog: “Buds, Bugs, and Birds in the Manuscripts of Esther Inglis.”

“Little Beasts” is on through 2 November – go if you can, and check out their website for much more detail: https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/little-beasts-art-wonder-and-natural-world