Our thoughts turn to ice and icicles in various forms these days, especially on the heels of a major storm. That reminded me of the term used by Esther Inglis in translating a series of French poems. The word is “yse-shok,” one I’d never seen before. Turns out it’s an old Scots term for “icicle.” It can be spelled various ways, and according to the Dictionaries of the Scots Language, comes from Danish and Norwegian terms isjokkel and isjøkul via German îs-jokel, and Middle English ise-yokel.

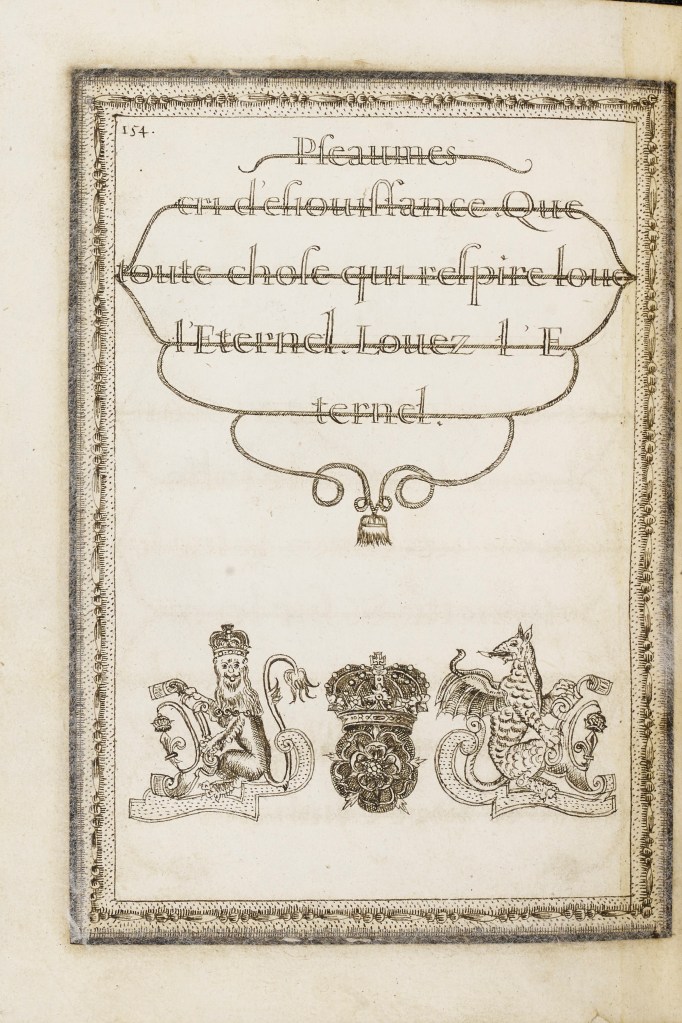

The poem in which she uses the term is part of a cycle of 50 Octonaires sur la Vanité et Inconstance du Monde (Octonaries on the Vanity and Inconstancy of the World). They were written around 1570, by Antoine de la Roche Chandieu, French Protestant theologian, diplomat, and man of letters. The poems became quite popular, circulating in manuscript and print, set to music, and going through many editions well into the 1630s.[i] The purpose of the cycle was to remind Protestants to keep the faith: not to let themselves be led astray by all the fleeting attractions of this world, but to keep their focus on God. Thus they could live a good life and hope for salvation from Christ.

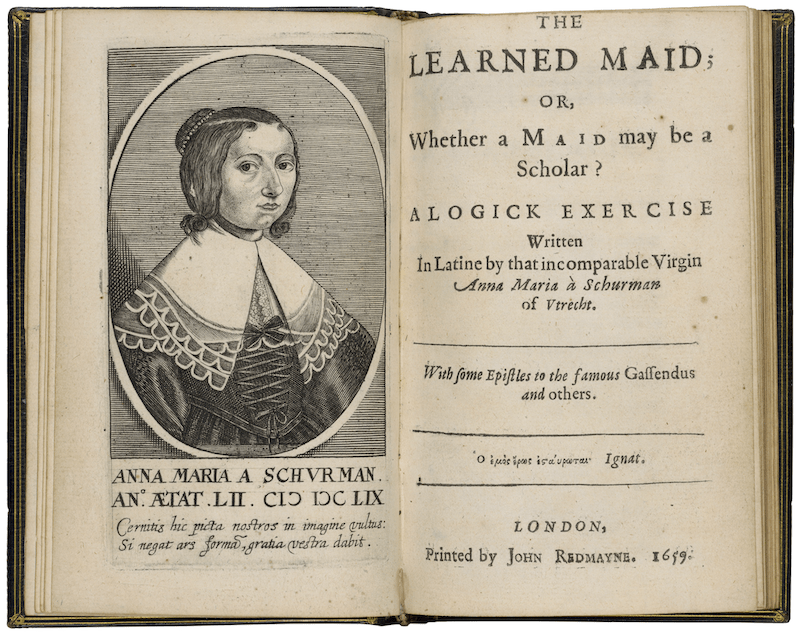

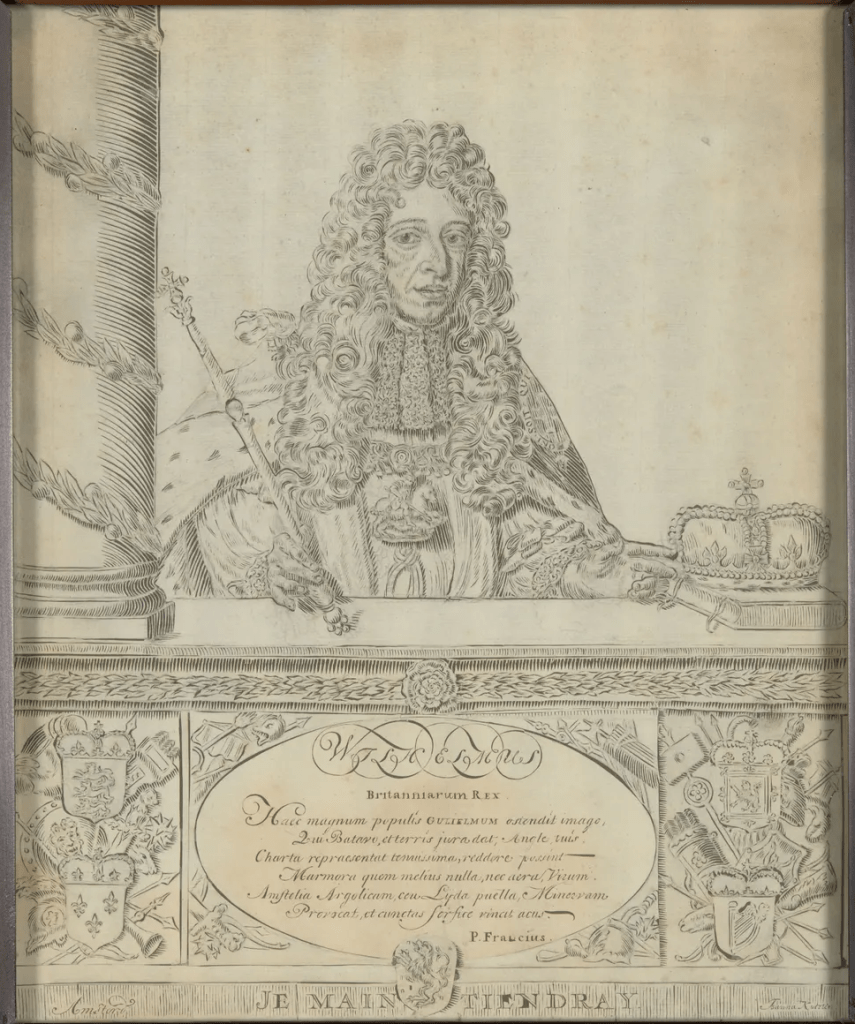

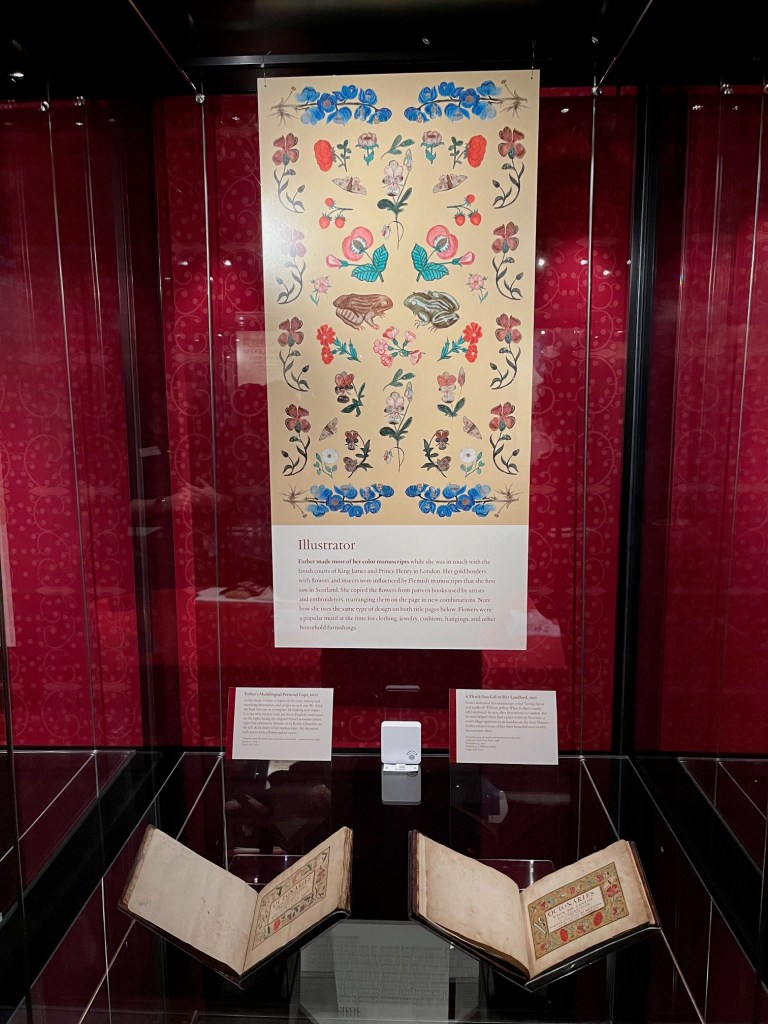

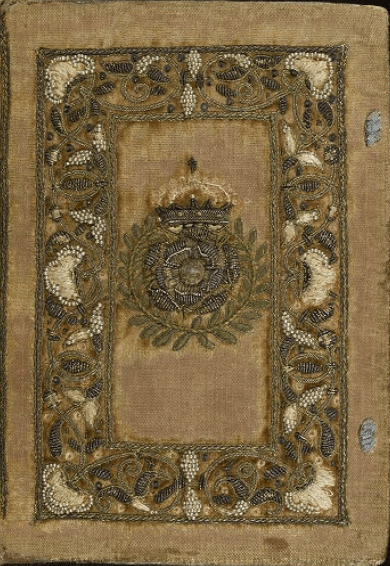

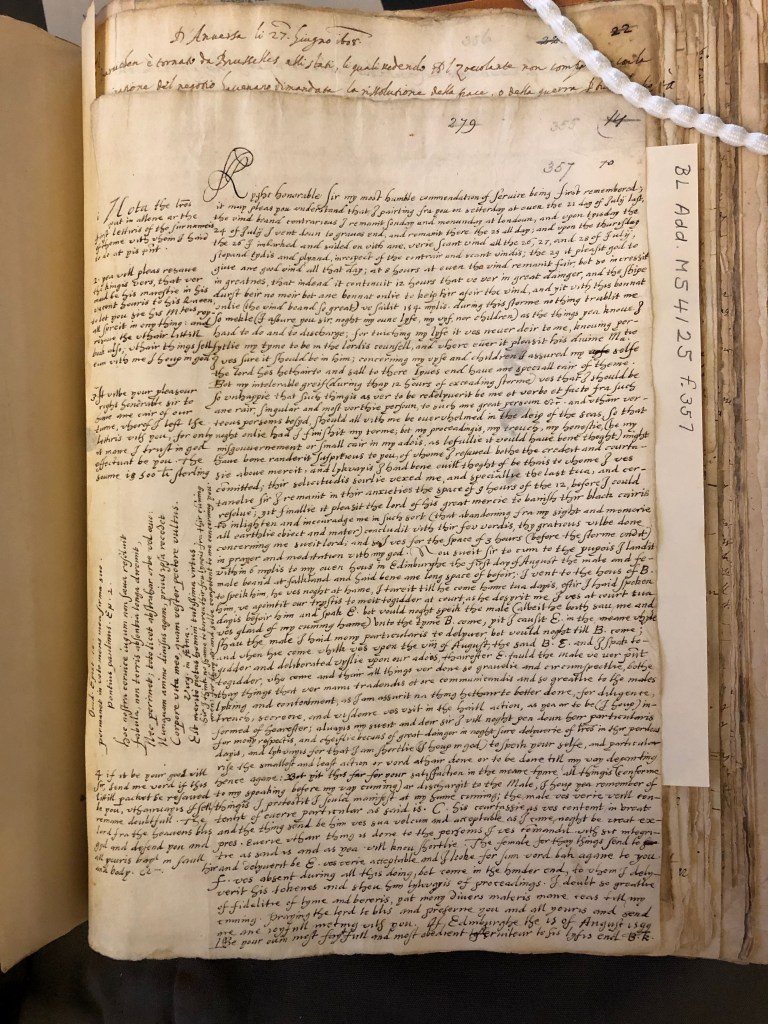

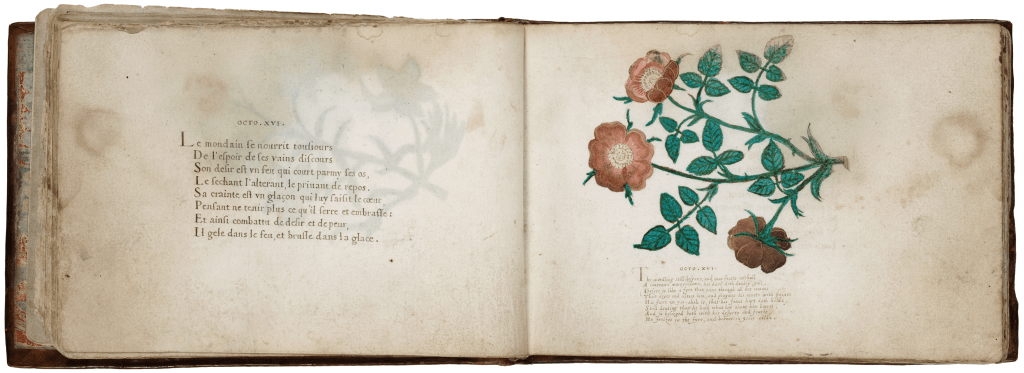

Strange as it may seem to us, the poems also proved to be a popular New Year’s gift, and Esther presented several of her beautifully decorated manuscript ones in this way. She wrote out at least nine copies in French and three in “Anglo-Scots.” The French ones she gave to a number of prominent Scots including Prince Henry (seen above) and Prince Charles, the sons of James VI and I. Her translation went to her Mortlake landlord, William Jeffrey (1607), and to John, 1st Baron Petre, the major landholder where she lived while in Essex (1609).

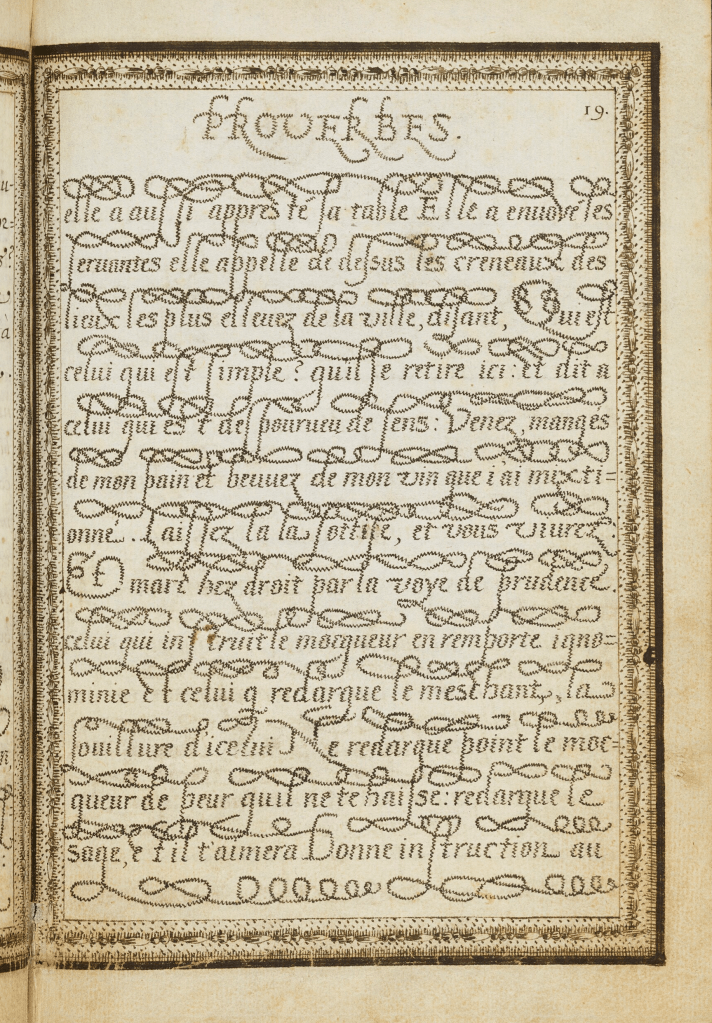

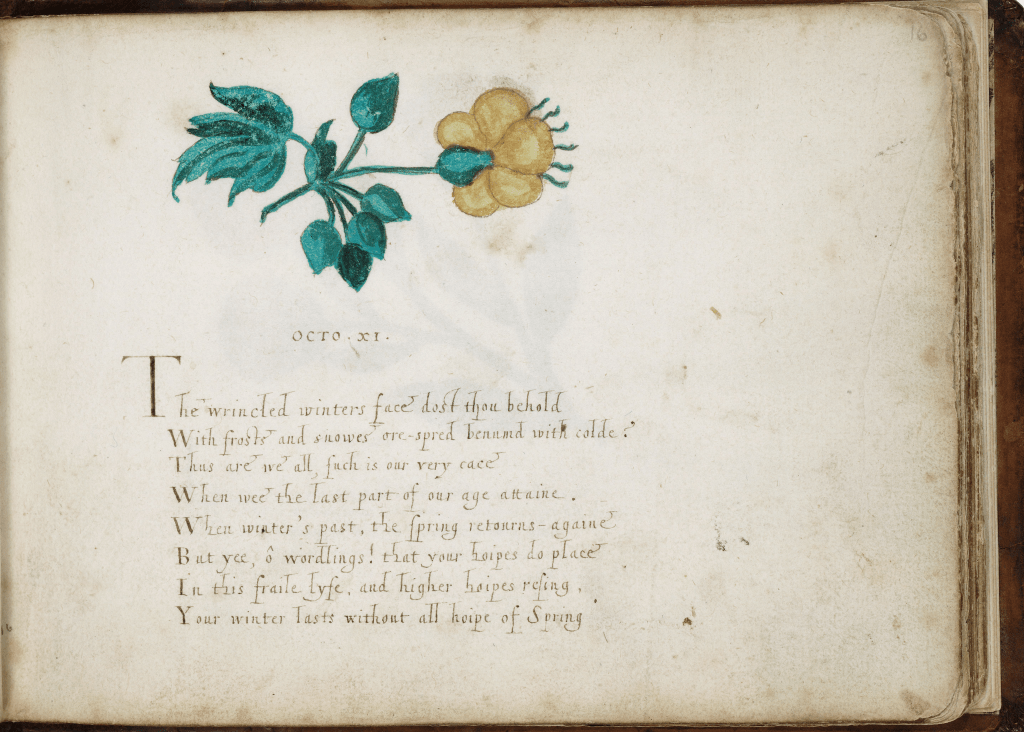

Near the beginning of the Octonaires, Chandieu devotes four to the seasons of the year, numbers VIII through XI. Here is Esther’s translation of winter (seen above), where her summer flower on the page contrasts with the season:

OCTO. XI.

The wrincled winters face dost thou behold

With frosts and snowes ore-spred, benumd with colde?

Thus are we all, such is our very cace

When wee the last part of our age attaine.

When winter’s past, the spring returns againe,

But yee, o wordlings! that your hoipes do place

In this fraile lyfe, and higher hoipes resing,

Your winter lasts without all hoipe of Spring.

The theme of winter and spring reasserts itself with reflections on cold and heat in Octonaire XVII (XVI in Esther’s version).

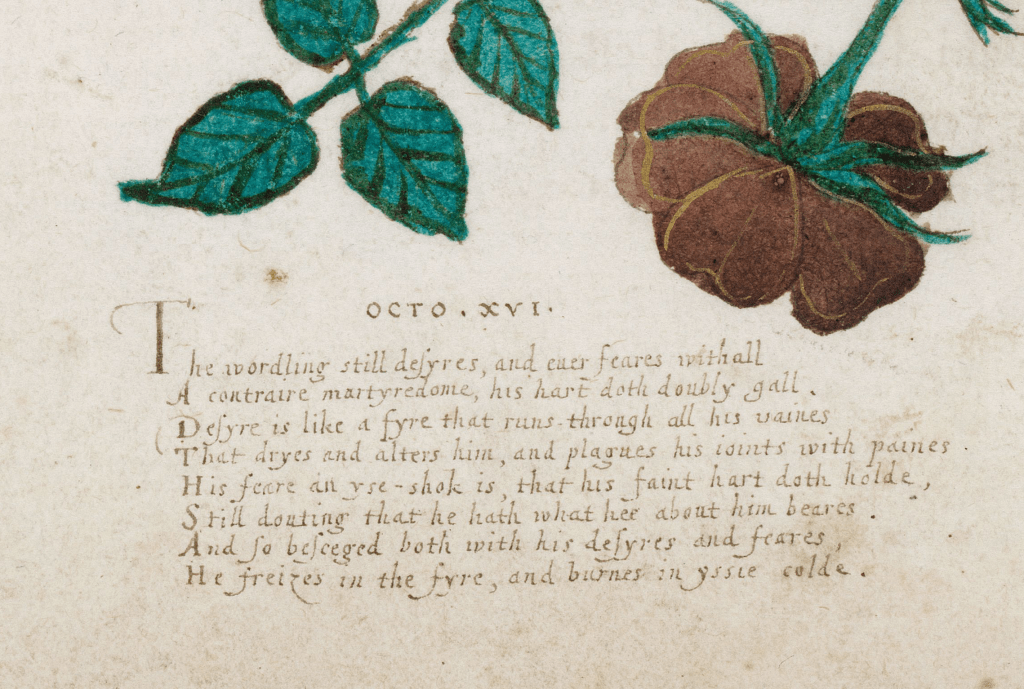

OCTO XVI

The wordling still desyres, and ever feares withall;

A contraire martyredome his hart doth doubly gall.

Desyre is like a fyre that runs through all his vaines

That dryes and alters him, and plagues his ioints with paines.

His feare an yse-shok is, that his faint hart doth holde,

Still douting that he hath what hee about him beares.

And so beseeged both with his desyres and feares,

He freizes in the fyre, and burnes in yssie colde.

The contrast between the two extremes was commonly used in Renaissance love poetry to describe how lovers feel when confronting the fires of their passion and the icy regard of their mistress. Here’s an example from Spenser’s sonnet XXX from his Amoretti:

My Love is like to ice, and I to fire:

How comes it then that this her cold so great

Is not dissolved through my so hot desire,

But harder grows the more I her entreat? . . .

But Chandieu, and Esther have taken the hot-cold, fire-ice metaphor and used it to describe the heated vain desires of a worldly person – “wordling” – versus the icy fear that they might be losing all their worldly possessions. Esther translated the French “Sa crainte est un glaçon, qui luy saisit le coeur,” (His fear is a piece of ice which seizes his heart) as “His feare an yse-shok is, that his faint hart doth holde.”

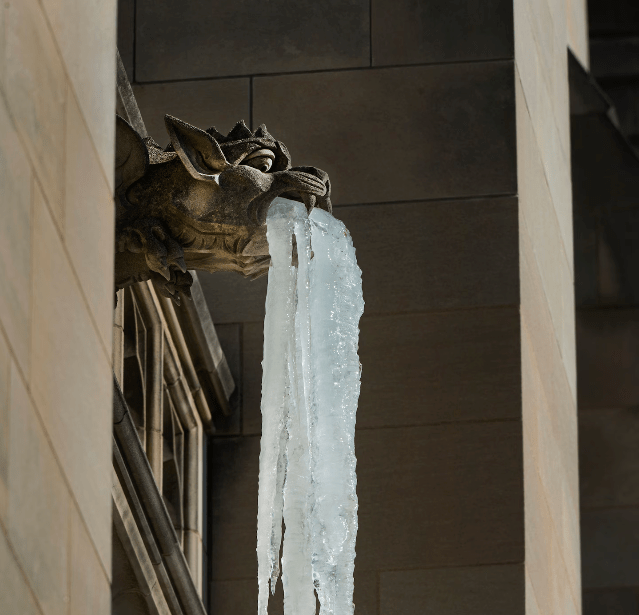

Robert Henryson and Gavin Douglas, two great earlier Scottish poets, used the term in its literal “dripping frozen water” sense. Henryson in his Testament of Cresseid (c.1500) describes the personified “cold” planet Saturn, “The ice schoklis that fra his hair doun hang/ Was wonder greit, and as ane speir als long” [as long as a spear]. Gavin Douglas in the Eneados, his 1513 translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, describes the huge figure of Atlas “baryng on his crown the hevyn”: “Furth of the chyn of this ilk hasard auld [same old man]/ Gret fludis ischis [floods issue], and styf ise schoklyllis cauld [stiff icicles cold]/ Doun from his stern and grysly berd hyngis.”

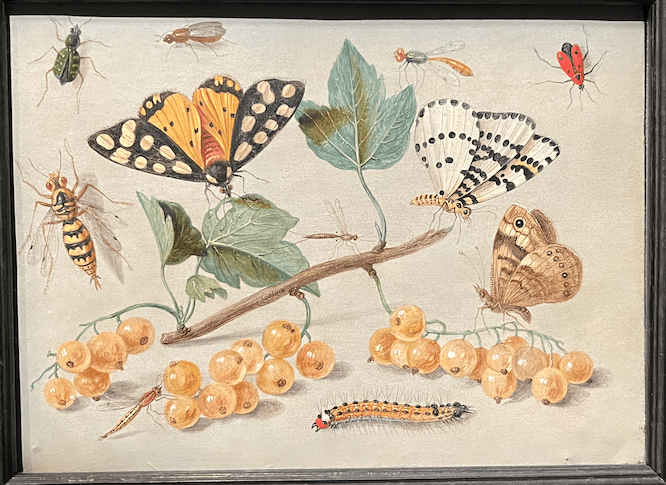

Esther and her family lived during what is now known as the “Little Ice Age” when European winters were especially cold, and frost fairs were held on the frozen Thames in London. Dutch artists in the period were especially fond of depicting life on ice, as seen in this landscape (1608) by Hendrick Avercamp with skaters, ice-hockey players, and sleigh riding, along with people trying to carry on their daily lives in the cold. A detail of the building on the left shows “ice schoklis” (ijskejels in Dutch) hanging from the eves.

[i] See Jamie Reid Baxter, ‘Esther Inglis: Franco-Scottish Jacobean Poet and her Octonaries upon the Vanitie and Inconstancie of the World’, Studies in Scottish Literature, 48.2 (2022) https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2315&context=ssl